Never in my lifetime have so many been wondering:

- Why should evidence be given against the accused?

- What right do criminals have to know the nature of the accusation?

- Shouldn’t we spare the expense of a speedy and public trial?

- Why a jury of peers? Don’t the judges know the law?

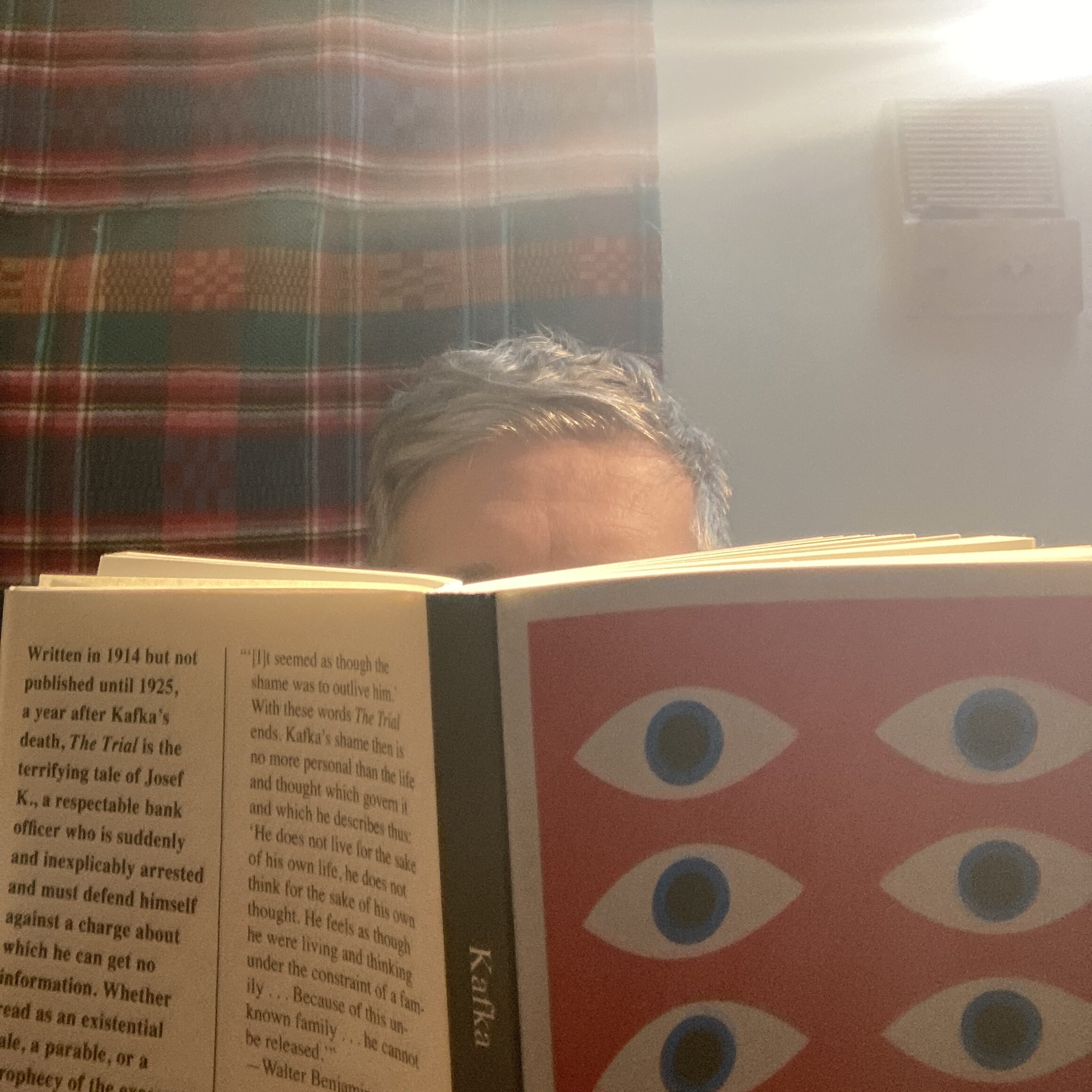

For the answer we can look to Franz Kafka’s novel The Trial, published 100 years ago. It’s not a pleasant journey but it has never been a more necessary one.

Josef K. is caught completely by surprised when he is arrested one morning. He is informed that he will be tried, though not by whom or for what. He is allowed to go to work and remain at home, and at first appearances he seems free. But as the trial continues, we see that he could be no less free if he were in the deepest hole in El Salvador.

Mr. K. is oppressed by the duties of his defense, which he must guess at, since deliberations on his case and even the charge are kept entirely secret from him. These various attempts disrupt every aspect of his life. Still, he must keep at it, he does know that inaction will mean doom. Even offers of help, from strangers or from friends, or from the lawyer his uncle engages, are to no avail and only form another knot in the bonds that tie him.

Under the nameless foreboding of a massive, authoritarian bureaucracy for over a year, Mr. K loses sleep, slips up at work, and quarrels with his neighbors. The court’s operation is opaque and unswayed by facts, he can only hope to make some personal connection with someone knowledgeable of the case and/or the respect of the judges.

In short he has no right to discovery, he cannot face his accusers, he has no right to a speedy and public trial by his peers, he cannot file a writ of habeas corpus demanding the reason for his detention.

Consider that Kafka wrote the novel in 1914, though it was not published until after his death. The word fascism does not appear, that movement was only just getting started in Italy. Kafka wasn’t satirizing Hitler or Mussolini or Stalin, they were not people he would have heard of. It didn’t start with them: these are the things people with unchecked power do to one another.

Note that we never find out what the crime was, and we really don’t know if Josef K. is guilty. We only know his attestations of innocence and his confusion at the proceedings.

An accusation can be levied at anyone, at any time for any reason. Without due process for uncovering facts, it is illegitimate. If you don’t bring evidence, if you don’t think you can convince a jury, if you don’t allow the accused a competent defense in a speedy, fair, and public trial, you don’t know what happened. All you have is your preconceptions.

And well, that’s just like, your opinion, man.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.